This academic year, at MICSEA, we held a lecture series called Reflections on the Field which we shared the experience and knowledge of a wide range of professionals who work in the Humanitarian field and who through their offices and organizations offer internships to our students. Our program is intimately linked to real scenarios, addressing conflict and emergencies worldwide. This insightful part of the program is developed thanks to the collaboration we have established with many of the most relevant Humanitarian organizations such as IOM, IFRC / ICRC, UN Environment Programme, UN Habitat, UNICEF, among others. At MICSEA it is crucial to engage our students with real contexts from the beginning of the academic year, first through local and international workshops and, later, helping to gain practical knowledge at our partner organizations in the area of international cooperation.

In this post, we wanted to share the reflections from some of the partner institutions in which our students are currently developing their internships, and so we are very happy to share the interview MICSEA had with Joseph Ashmore from IOM, Isabel Parra from UN-Habitat and Teddy Cruz and Fonna Forman from Estudio Teddy Cruz + Fonna Forman.

1. How do you think this Master helped students acquire skills in the humanitarian and social architecture field?

Teddy & Fonna. There is no better classroom than working in-situ. MICSEA is an excellent program since it combines classroom learning, design studio and a field-based internship that orient students to the theories, design and practices of emergency architecture.

IOM. The main learning from any course is about the process: how to approach problems and find ways forward. A lot of the work in humanitarian programming is not very “architectural” – in humanitarian shelter response, we are more likely to be figuring out how to get plastic sheeting to people than designing a structure, and even when we design a structure we are more often asking local builders to do it. As a result, the skills in approaching a problem, or analyzing what has been done gained from the course are more important than structural design skills in humanitarian response. That being said, sometimes you do have to draw up a timber shed at short notice and design skills are useful for this. The course also provided a theoretical background on some of the issues in relation to the built environment.

UN. Undoubtedly, the students have contributed to our work with a critical view of UN-Habitat’s resilience tool. In particular, they have highlighted the need to stress more on issues of informality and the gender gap, which directly relate to their research.

2. What has your experience been collaborating with MICSEA students and alumni? What profiles of students are often involved in your field?

T&F. Our experience with MICSEA students has been excellent! They come with unique skills and passionate commitment to social imperatives of architecture. Many of them have had prior experiences working in contexts of challenge and marginality and are eager to learn new sensibilities and skills in our context, at the US-Mexico border.

IOM. We have had many good students from the course with profiles strengthened by several years in “The field”. All of them have wanted to go back to operations and see Geneva as a stepping-stone rather than a destination. They have all been awesome!

UN. MICSEA students are highly proactive and have an innate `hunger’ for knowledge. They constantly challenge our way of doing things and, most importantly, bring new perspectives to the table. They often act as a “bridge” between the technical and the advocacy team, evidencing their capacity to adapt and integrate ideas and stakeholders. Throughout these years of collaboration, we’ve had students with high technical skills and essential soft skills such as assertive communication, proactiveness, and self-motivation.

3. What is your perspective on humanitarian architecture considering the increase in conflicts, forced displacement and climate emergencies?

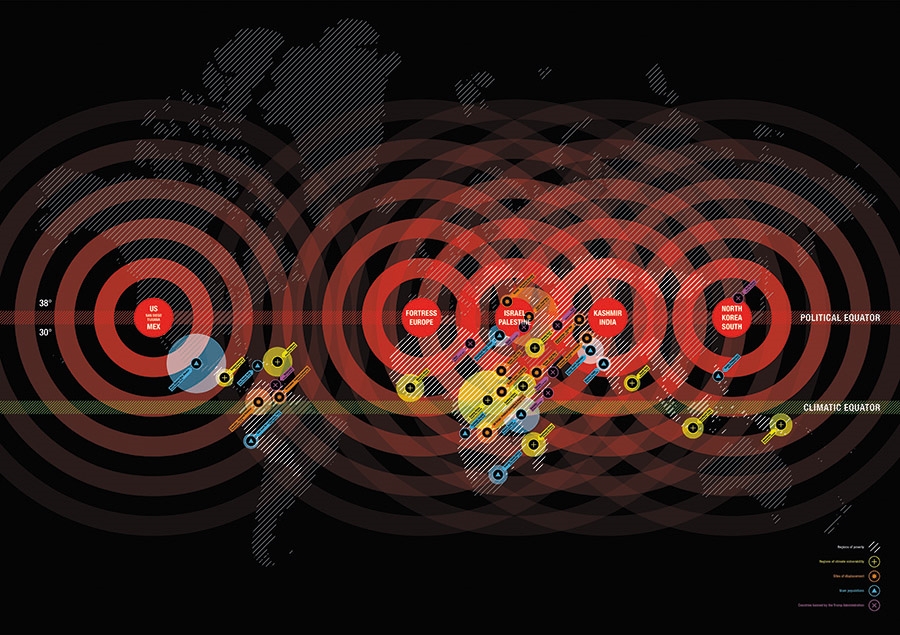

T&F. We believe that neutrality is complicity and that architects need to take a position on today’s unprecedented challenges — geopolitical conflict, deepening inequality and injustice, and the accelerating impacts of climate change across the world — and practice accordingly. We need to decide when, and when not, to build – and recognize that we can do more as architects than decorate injustice.

IOM. There is an increasing need for socially and climate-aware built environment professionals. A lot of responsibility lies on the consumer side in “developed” countries where per capita carbon emissions are hundreds of times higher than for the world’s most vulnerable people. In crises, with 100 million displaced by conflict, plus equivalent numbers of people affected by disasters annually, there is a need for efficient use of limited resources to ensure quality programming at scale and to advocate for those people affected. There are even larger amounts of work to do in relation to the billions of people living in poverty or substandard accommodation with chronic “development needs”. This requires highly motivated, committed and skilled people with diverse skillsets. Whilst it may be hard to get first jobs to start “careers”, there will be many many roles in the future that require the skills and Experiences that MICSEA students bring.

UN. Humanitarian architecture is at the heart of our work at the City Resilience Global Programme of UN-Habitat. The recent ongoing global crises caused by COVID-19 and the invasion of Ukraine have set the world back from achieving the 2030 Agenda’s goals and targets. Humanitarian architecture with an emphasis on resilience building is essential to recover from the current crises and prepare to better respond to the next one. Achieving the SDGs requires new professionals—able to scale action while promoting integration and collaboration.

If you were wondering what our alumni are doing and what the professional outcomes are after studying MICSEA, we hope this post has answered your questions, and at the same time enhanced the need there is for learning a new set of tools and methods at an architectural and urban scale in order to make a difference in the fields of emergency and development.