- Dear Apen, you are an anthropologist specialized in heritage and community building and gender perspective in urban development. Do you believe there is a need to increase the collaboration between anthropologists and urban planners for the design practice to reflect upon the socio-economic necessities of populations?

I have been working with urban planners and architects at UIC for the last few years. This collaboration addresses a fascinating perspective on how to understand urban space. The technical way they approach the space and the city is crucial. At the same time, they take many things about human behavior for granted. For example, architects focus more on the socio-economic perspective or the practical side, but emotionality is rarely considered. This is one of the reasons I believe this collaboration is essential in terms of methodology. Both disciplines bring elements and methods very relevant to understanding urban practice in a complex way, so it would be interesting to involve them in both realms from an early stage of the studies.

- Every year you teach a seminar on Gender, Space, and Culture in our Master’s program. The role of feminism has become key for building a better and more just future. How do you tackle this broad subject in regards to spatial practice?

The course I am teaching here at MICSEA is relatively short; I try to provide them with research sources to keep on investigating. To me, gender and feminism are transversal work that crosses all the topics of this Master; it should be implemented throughout all year. From my approach, I try to differentiate gender as a subject of study (that is, the position of women doing research or in the humanitarian practice), and, on the other hand, the implications of gender issues in situated scenarios. Then, when it comes to academia, architecture, or urban planning, it is not a question of a ‘subject of study’ but how you situate yourself within that specific context. For whom are you designing and with whom? In this sense, there is a lot of revisioning of the practice that needs to be done. In the masters, when it comes to emergency architecture, a gender perspective is crucial because of the repercussions concerning each identity. To me, feminism is a matter of understanding the theory and bringing awareness into any practice.

- It seems that current generations are more aware of the necessity of implementing gender issues in urban developments. How do you see this evolution when it comes to our students?

It is very challenging in a good way to teach this course in the masters because they are very international students. They come from extensive cultural backgrounds and contexts; just acknowledging various approaches to their own gender identities or how feminism is understood in each different cultural context and to discuss this in the class is very enriching. For example, when I give them articles from feminist scholars to read, they sometimes find themselves uneasy with subjects such as emotionality. I feel I shake them to confront perspectives they didn’t realize before. Lately, several final theses have been working with gender as a central topic, which is valuable in new generational perspectives. They are very open to embracing feminism, but they still need guidance.

- For the last two years, you have been working on how the COVID-19 crisis affects the most vulnerable populations and our social structures. Which are your reflections upon gender equality and social justice during this period?

This is a topic in a very early stage. There will be many outcomes in the future, and more research should be done. Nevertheless, one interesting analysis in the cases of strict lockdown is gender relations in the households. What happens with the kids? Who takes care of them? How to integrate work in the domestic environment? Mainly, it is relevant in traditional heteronormative families, where there are fixed patterns. Issues like gender violence or working remotely in this context have brought over the table the question of intimacy and domestic spaces

Another question is the vulnerable population worldwide – mainly in the global south. Women and people make their living out of resources that have been restricted due to COVID-19. How is the system in terms of health o food security, especially for women who are the most affected? Like any kind of crisis, it should address this gender perspective because women and men are not under the same conditions.

- From MICSEA, we actively support the ‘Woman in Selter’ group, which represents women’s needs and conflicts in the Shelter sector. Could you briefly explain current debates and strategies to implement gender issues in the humanitarian field as a group member?

- How do you see the future of architecture and urban practice as an anthropologist?

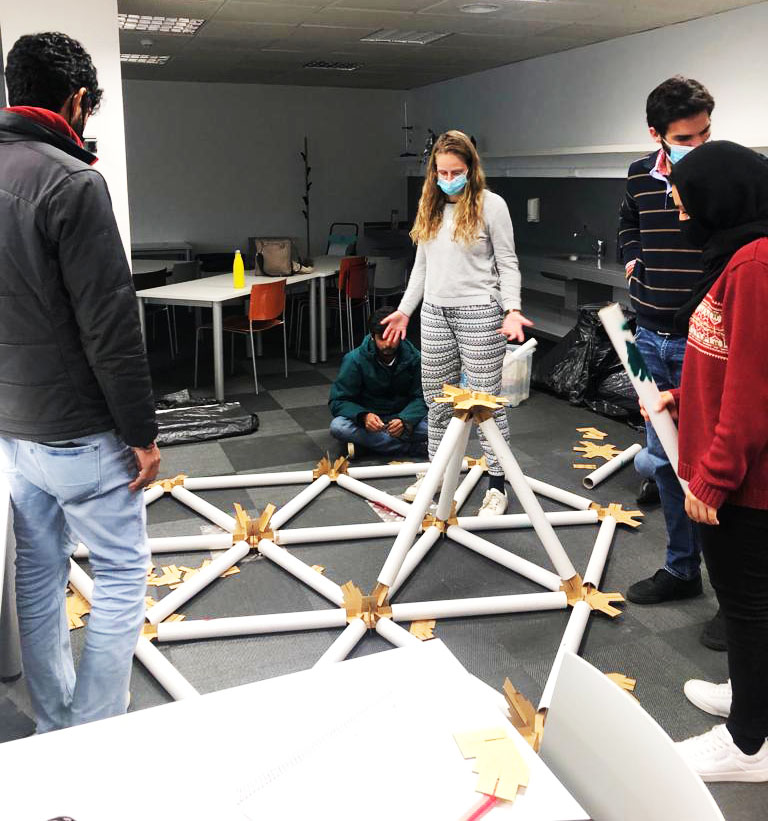

I have a partial approach to architecture since the Master’s program significantly mediates my relation to the discipline. However, I appreciate how rigorous and accurate their work and methodologies are, and I think the future is illuminating in working cross-disciplinary and collaborating between both realms. In this sense, the workshops we are doing here are very interesting examples in terms of gathering different sources of knowledge with successful practical experimentations. The practice of architecture is very empowering but sometimes too hierarchical. Then, providing other tools is very enriching, broadening their perspective. A the end, the openness to democratize the ways of doing is also a matter of feminism.