Former student Dana Barqawi asks this question in a recent article in which she advocates for planning cities rather than camps, as a much-needed long-term approach to housing refugees. It’s a view shared by many aid experts in light of the protracted situation experienced by most camp dwellers.

Former student Dana Barqawi asks this question in a recent article in which she advocates for planning cities rather than camps, as a much-needed long-term approach to housing refugees. It’s a view shared by many aid experts in light of the protracted situation experienced by most camp dwellers.

An architect from Jordan, Dana completed our master program in 2016. After working in Nairobi, Kenya for 4 months to work with UN-Habitat developing an Sustainable Development Goal monitoring tool called the City Prosperity Index, she took up a position with German NGO BORDA (Bremen Overseas Research and Development Association) in its regional office in Amman, Jordan, developing, implementing and disseminating decentralised sustainable technologies and social measures for water, wastewater, energy and waste in underprivilaged communities.

She says her interest in refugee camps led her to her current work with infrastructural development.

“To a lot of people, it sounds like I’m jumping between different fields of study and work, but to me, it makes complete sense. In the end nothing works in isolation; we live in a system in which everything is defined by its interconnection with everything else.”

Having observed the refugee situation in her native Jordan, she says, “So much money, time and energy is being poured into creating ‘temporary’ camps rather than improving the stressed infrastructure, be it social, economic or environmental. Governments need to realize that the refugee situation is not just a temporary humanitarian crisis, but a long-term development issue.”

Below is a repost of Dana’s article, orignally published at her Linkedin profile.

Why Do We Still Build Refugee Camps ?

A short while ago, a 55-second BBC News air footage of the Syrian Zaatari Refugee Camp went viral on social media pages because of its shocking revelation of the size and density of the camp, which makes it the third largest camp in the Middle East and the fourth biggest “city” in Jordan.

A refugee camp’s life span lasts for an average of 17 years, according to the UNHCR, and even most of them last much longer. Given that camps are unlikely to be truly temporary, and also that “over 60 per cent of the Syrian refugee population in the region live outside camps” (UNHCR), the apparent question is why do we still build refugee camps? And why are funds still flowing into them rather than push for more resilient solutions?

Seven years ago, September 2009, the UNHCR’s Policy on Refugee Protection and Solutions in Urban Areas called for the pursuit of “durable solutions” for displaced persons to benefit both the host countries and refugee populations. Yet, materializing paper policies on the ground can be a little more complicated, and old habits die hard.

Camps are still plenteous, and they are central to UNHCR’s plans. Despite the UNHCR commending a more sustainable and resilient solution towards influxes of displaced persons worldwide, the Western funding and “out-sourcing” of large-scale refugee camps to third world countries has continued, keeping émigrés outside European borders, and putting them in a state of permanent temporariness, and their host populations under enormous political and socio-economic pressures; “Four-fifths of all refugees are in the developing world, in nations that can least afford to host them.” (United Nations)

“…more than 80 percent of the world’s displaced people are in developing countries. By funding UNHCR and other aid agencies, the world’s wealthiest countries pay to keep them there”

Elizabeth Dunn, Boston Review, September 28, 2015

The main claim for building camp-sites is that logistically camps make it easier to channel help, services and support to displaced persons when they are gathered in one place, But how efficient is this when “the reality is that only one-third of the world’s 10.5 million refugees still live in camps. The rest have been steadily moving to cities and towns.” (UNHCR)

The reasons, displaced persons are held in camps, are as much political as they are humanitarian. Camps reduce the tendency of people fleeing westward to seek refuge, and they offer politicians and decision makers an alibi to bypass involvement with foreign war decisions and domestic exodus matters.

But with no end in sight to the mass flight of refugees from war-torn countries they once called home, the refugees are staying and will continue to stay and form spaces that are stuck between being humanitarian spaces and makeshift cities, whose bareness and lack of services make them a chronic mess.

A Long[er]-term Solution

Zaatari Camp was constructed in July 28, 2012 by the Government of Jordan and international agencies as an emergency response to the protracted Syrian conflict to which the return period is still unknown. It is being called a “crisis”, suggesting that the status is short-lived. Thanks to the trajectory of the current events which are a product of greed, selfishness and trivial political agendas, the numbers of refugees are not going down.

The temporary structure of Zaatari Camp is designed to respond to a temporary emergency demand and then disappear. Compared to long-term solutions, the preference is to channel refugees into camps and pend their repatriation, sometime. Yet there is no hint that the Syrian refugees will be repatriated or resettled in any other place any time soon.

Jordan is a country scarce on resources and capital, and the huge influx of refugees puts a lot of strain and pressure on the socio-economic fabric and the already weak and unreliable infrastructure.

The Jordanian Government, international and national communities must commit to implementing a sustainable solution in response to the current instability in the region. Inclusion of refugee persons in national development agendas, even though challenging, is crucial to the sustainable and resilient growth of the country.

The need is for major international commitment to capitalize on opportunities in host countries to channel the flow of aid funds towards helping the government to invest in longer-term infrastructural development rather than pour billions into building temporary and inhumane refugee camps which become deeply-rooted diseased cities.

According to The UNHCR, around $250m of aid funds were spent in Jordan in the first half of 2013. Yet, low-income Jordanian citizens are still bearing the impacts of the refugee flows. The challenges imposed by the Syrian crisis on the host Jordanian populations range from burdens on local labour, investment and education to health, housing, water and agriculture.

A Growth Node

Syrian refugee camps are located in underdeveloped parts of Northern Jordan, and the out-of-camp refugees, who live in urban and peri-urban settings, choose to live in lower-income neighbourhoods in Jordanian cities which creates further challenges and pressures on the low-income citizens in those areas.

Alternative to continuously funding temporary camps, the influx of aid should be channelled to create real cities—places with sewage, electric and water infrastructures, schools, houses, public spaces and civic institutions—to stimulate local economies, create livelihoods, and make it possible for governments to look at the situation as an opportunity instead of a burden.

The idea builds on “adapting” and “enhancing” existing infrastructure (socio-economic and physical) to meet the demands of the refugee situation in Jordan as well as the demands of the Jordanian citizens. It is about finding the correct intervention points which could leverage and trigger a series of responses to invest in large infrastructure development projects that could advance the country’s growth.

Diagram representing a 4-phase strategy envisioning infrastructure as a catalyst for improved livelihoods for locals and refugees alike, and for a sustainable development and growth of the country.

The existing agglomerations become “Growth nodes” that host new functions and infrastructures to meet the demands of local and refugee populations. They provide the amenities and services that are usually missing in lower-income Jordanian neighbourhoods, villages and out-sourced refugee settlements.

The strategy stems from existing site conditions and offers benefits for a growing and conflicted community. Infrastructure is the point of sustainable urban development, it defines growth patterns, catalyses and becomes the first piece of a resilient future urbanization process. External support for refugees will benefit host communities, as funds go towards improving the infrastructure and capacity of local facilities.

The objective is to provide immediate relief whilst providing longer-term sustainability for host communities.

The objective is to provide immediate relief whilst providing longer-term sustainability for host communities.

Jordan desperately needs to invest in infrastructural development schemes, but instead cash is being swallowed up into grey zones that are neither temporary nor permanent.

Even though it is important to note that a challenge lies in the fact that political factors and agendas do have a bearing on how development is theorized and exercised, what the Jordanian government, international organizations and other host countries, cannot afford to do is wait for scenarios like the “end-of-warfare” to happen, and for the masses to return home.

We are not building camps we are building cities.

We need to plan as if they will stay forever.

Dana Barqawi is a multidisciplinary architect & strategist from Jordan specializing in international cooperation and urban development, with international training and experience across Europe and the Middle East. She currently works at BORDA, the Bremen Overseas Research and Development Association founded in 1977 by planners, engineers, business people and social scientists as a civil society expert organisation devoted to providing disadvantaged urban populations access to essential public services such as energy, sanitation, waste management, and water.

Dana Barqawi is a multidisciplinary architect & strategist from Jordan specializing in international cooperation and urban development, with international training and experience across Europe and the Middle East. She currently works at BORDA, the Bremen Overseas Research and Development Association founded in 1977 by planners, engineers, business people and social scientists as a civil society expert organisation devoted to providing disadvantaged urban populations access to essential public services such as energy, sanitation, waste management, and water.

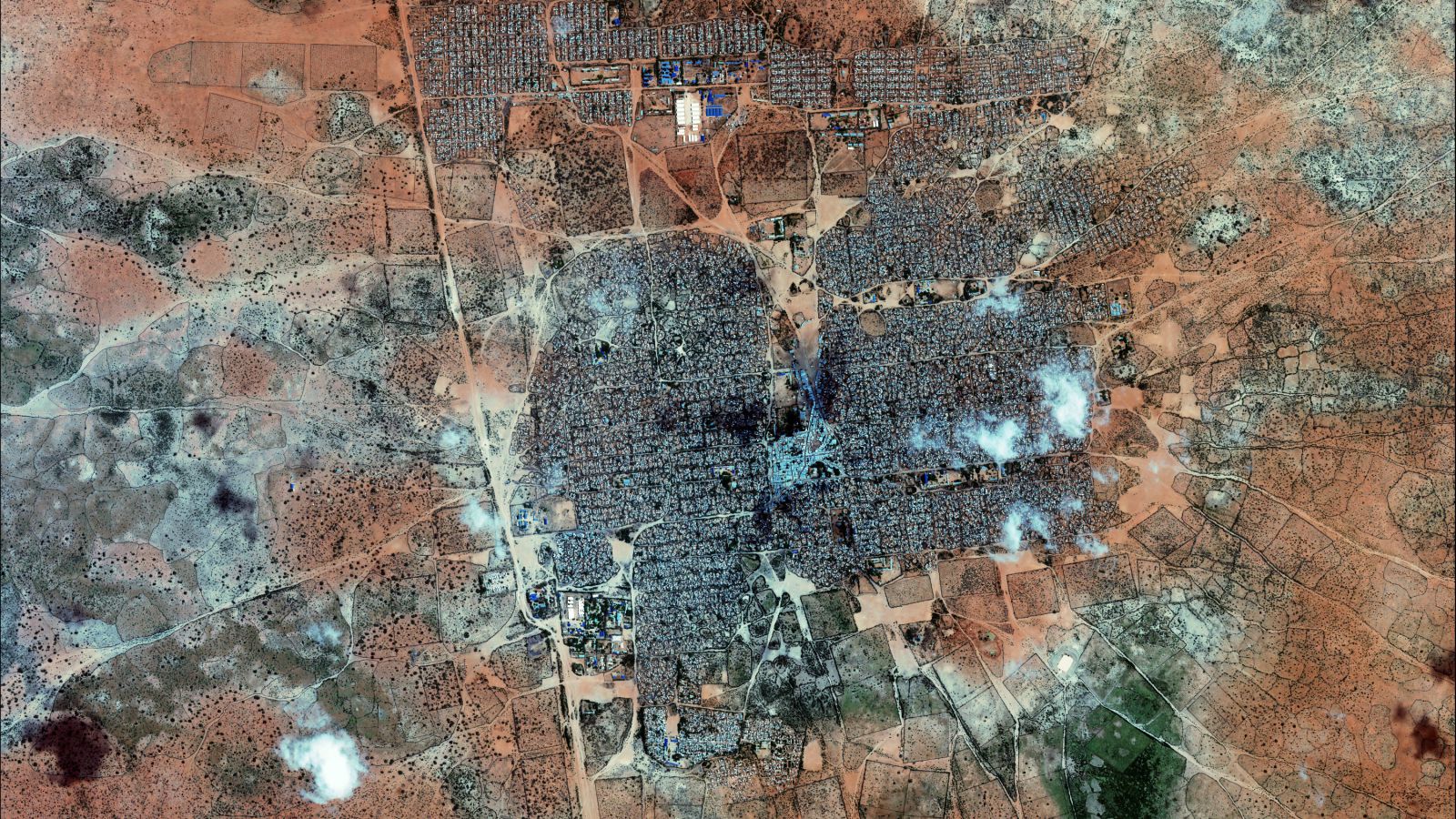

Top photo: The Dadaab (Dagahaley) refugee camp in Kenya. (DigitalGlobe)