Alejandro Haiek downplays his role as architect in defense of a slow yet transformative architecture ultimately powered by the community.

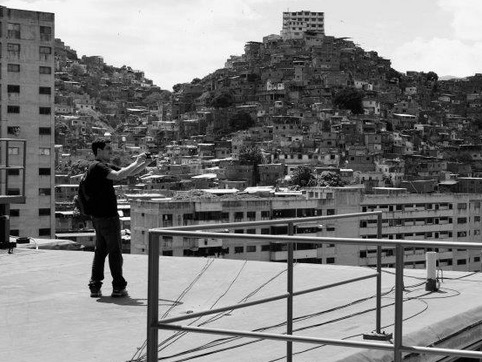

Last November, we welcomed Venezuelan architect Alejandro Haiek as visiting professor of our program with a week-long workshop on Governance, Participation and Social Design. As cofounder of LAB.PRO.FAB, his bottom-up practice relies on the occupation and reactivation of abandoned urban spaces in order to provide much-needed sport facilities, cultural centers and public plazas in the informal barrio communities of Caracas. The studio’s work has been recognized for its non-hierarchical approach to participative design, its integration of local knowledge and craft, and its capacity to bolster social ties and stimulate micro-economies.

Last November, we welcomed Venezuelan architect Alejandro Haiek as visiting professor of our program with a week-long workshop on Governance, Participation and Social Design. As cofounder of LAB.PRO.FAB, his bottom-up practice relies on the occupation and reactivation of abandoned urban spaces in order to provide much-needed sport facilities, cultural centers and public plazas in the informal barrio communities of Caracas. The studio’s work has been recognized for its non-hierarchical approach to participative design, its integration of local knowledge and craft, and its capacity to bolster social ties and stimulate micro-economies.

We sat down with Alejandro to probe into the motivations and mechanics behind his practice.

How did you become interested in achitecture and social impact?

It has a lot to do with the fact that both my mother and father were civil engineers and also particularly influenced by art, culture and music. Their work was always tied to social causes, such as public housing, and that is something I found very interesting; how a technical profession and scientific knowledge could have direct applications on social issues.

Bringing purpose back to science.

It seems that the more we advanced technologically, the more deteriorated we became as a society. This just didn’t make any sense, especially in a cosmopolitan city like Caracas, where the wealth generated by the oil boom of the 50s and 70s marked a path for the future, and at the same time constantly reminded us of everything that was going wrong: poverty, homelessness, class inequality, the informal economy… I admired how my parents were able to orient their knowledge to tackle these problems.

The Programmatic Platform, also referred to as the Spaceship, is a multifunctional space that combines, cultural, sporting and healthcare facilities. The collective transformation of the neighborhood has resulted in the rehabilitation of over 400 homes. © LAB.PRO.FAB

The Programmatic Platform, also referred to as the Spaceship, is a multifunctional space that combines, cultural, sporting and healthcare facilities. The collective transformation of the neighborhood has resulted in the rehabilitation of over 400 homes. © LAB.PRO.FAB

So both science and art are essential components of your practice.

As an architect I’m interested in art as an exploration of space, but also of values and ideologies. Architecture doesn’t’ offer the opportunity for critical reflection that art does. And as soon as these two things come together, we started to understand our work as more of a hybrid practice, which in turn enabled us to adopt a cross-disciplinary approach to encompass urbanism, industrial design, graphic design, landscape design and knowledge from other industries.

What was your first job as an architect?

My father was building social housing for a favela in Caracas, and he gave me the opportunity to design a series of playgrounds for children. After graduating in Architecture, one of my first projects was a prototype for social housing units.

Do you feel that experience led to where you are now?

Despite the opportunities that came through him, we never actually built anything together. Partly because I was really pushing the boundaries and he always thought my way of doing things was too extreme. In fact, before he died last year and seeing some of my projects, he said to me “You finally got your way. And you were right.” He liked that they had a very structural component guided by good engineering and that I was able to explore from within that space.

Back to the idea of science being at the service of society.

Yes, but technology alone cannot solve the world’s problems. It became clear to me that the problematics of contemporary cities do not lie in what is technically possible, but in what is socio-culturally desired.

Which brings us to what you refer to as designing “a logistical chain of events.” What do you mean?

There’s this conventional notion that the architect’s sole purpose is to build. A logistical chain of events refers to actions that may materialize as a building, but which initially serve to empower communities and allow them to generate cultural activities, establish a relationship with the landscape and create social associations and networks that prove much more important than the infrastructure of a building. We like to think we build human relations more than actual buildings.

Tiuna el Fuerte Cultural Park, winner of the International Award for Public Art, has catapulted young artistic talent in Caracas’s El Valle neighborhood. © Iwan Baan

Can you give an example?

When we began occupying the abandoned parking lot that would become Tiuna El Fuerte Cultural Park, the community knew they wanted a cultural center, but didn’t know what it should look like. Instead of proposing a design, we invited local performers–dancers, skaters, musicians, etc.–to start using the space as it was. This led to the creation of instant infrastructures that evolved and adapted to their needs in real-time. And the relationships that grew from this dynamic were crucial, because they guaranteed the continued use and appropriation of the center by the community.

It is a way of building the city that is far more flexible, gradual and adaptable than any large civic project that takes years to complete and paralyzes the social interactions of the site during that time. Our projects are living interventions, both construction sites and sites of learning that stimulate micro-economies thanks to their continual use.

The Botanical Plaza, supported by the state government plan and led by community members, features replicable constructive components created by local laborers. © Alejandra Loreto

The Botanical Plaza, supported by the state government plan and led by community members, features replicable constructive components created by local laborers. © Alejandra Loreto

How does a young architect go about finding this kind of work?

The same way you make a friendship. Architects are traditionally dependent on a client, but there are plenty of problems out there that need solving. We also need to rethink the way we approach the idea of work—do I sit it inside my office waiting for a client or do I go out there and talk to people, understand their problems and approach them like a fellow citizen who can apply their knowledge in solving them?

Is this what happened with Tiuna El Fuerte?

Yes, it started with us going to the neighborhood, attending their concerts and street gigs, and getting a conversation going. Together, we identified the need for a cultural center, and everyone began pitching in their know-how, from lawyers to musicians. We happened to be architects, but we were just one part of a large cross-disciplinary group of people.

And then what?

The first step was to revise the law and see what opportunities there were for the long-term legal occupation of an abandoned piece of land. The next step was to set up a program of activities that would be democratic and inclusive, so we invited the participation of community’s street artists who had been marginalized from the institutional art scene. Tiuna would become a platform for that cultural efferevesence that was present in every street corner of every favela in the city but that had no access to mainstream venues.

How did you find the money and resources to build up the site?

Practically everything was donated. We take advantage of the government’s social responsibility law that obliges companies to contribute in kind to social causes. Which is why we used shipping containers; not because they’re trendy, but because they were the building blocks made available to us. We also applied for government grants to develop different parts of the site.

Eventually, the workshops run at the center to teach carpentry and metalwork began to produce the components needed to continue building the site. So if we needed a window or a staircase, we would organize a workshop on building windows or staircases; that would be the exercise. It got to the point where we, the architects, were becoming less and less involved. The community itself began to take over building parts of the center, and we would just offer the technical support they needed.

How has it physically held up over time?

Behind this apparent informality is a formal process that integrates very precise protocols for security. We don’t reject the protocols upon which our cities are built; we want to reinvent them. We want to explore an architecture based on the availability of resources, and on an honest aesthetic that does not disguise but rather reveals the inner workings of the structures we build. A practice that is nourished by scientific knowledge and cross-pollinated with popular wisdom.

The lot of an unfinished building is now the Casa Cultural Simón Rodríguez, a popular meeting space for the community built with the support of the local government and participatory council. © Iwan Baan

What kind of difficulties do your projects run into?

The process can take a long time, people get tired…Some abandon the project against their will because of personal circumstances; it’s not easy to cross over to the other side of the system and be autonomous.

Other times an external actor creates an unbalance. In the case of Casa Cultural Simón Rodríguez, we managed to get funding from the mayor, which allowed us to finish the building, but which inadvertently caused the community to feel like they weren’t responsible for the project anymore. It’s something that tends to happen after so many years of populism. But in general I think the perception of what democracy should be is shifting from a representative model to a participative one that allows citizens to actively take part in policy-making through knowledge and action; a new collective model based on networked governability.

What’s the secret to LAB.PRO.FAB’s autonomy?

I think as practitioners we need to diversify, and we do that by being active in three main areas: development, dissemination and teaching. We combine our practice with anything from writing books, teaching workshops and speaking at conferences to applying for grants or conducting research that has a commercial application. Taking some commercial jobs may be a temporary option too, but fortunately we’ve been able to stop doing that to concentrate on the kind of work we really believe in.