Last month we featured one of our previous students, Nerea Amorós and her work in Rwanda teaching the country’s first generation of architecture students at the Kigali Institute of Science and Technology (KIST). As she mentioned in that interview, at the university she is currently working alongside colleagues from various architectural NGO’s, including Architecture for Humanity’s Design Fellow, Killian Doherty, who kindly sent us this urgent reflection on the importance of instilling regionalism in the practice of Rwanda’s modern architecture and recovering the country’s rich vernacular, stemming from a recent lecture by Peter Rich at KIST. The article was also sent to and published on Archinect.

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

In Search of a Rwandese Regionalism; ‘Learnt in Translation’ lecture by Peter Rich, Kigali, Rwanda 2011

Kigali context and Image of Kigali Masterplan model, Courtesy of Killian Doherty

Kigali context and Image of Kigali Masterplan model, Courtesy of Killian Doherty

‘The reality I have known no longer exists’ laments the narrator at the loss of the Paris of his youth. This extract from Marcel Proust’s ‘A la recherché du temps perdu’ (In Search of Lost Time), is referred to in Alexander Tzonis and Liane Lefaivre’s seminal essay ‘Why Critical Regionalism today?’ in an attempt to poetically capture the concept of the loss of a place and its identity. A loss synonymous with modern architecture, particularly in relation to contemporary global development , in this essay they argue for a ‘Regionalist Architecture’ , an architecture of place making which preserves the fibres of ‘collective social structures and the collective representations’[i] that are etched within community and place ; things that cannot be recaptured if lost.

Football for Hope Centre in context , Kimisgara, Rwanda. Courtesy of Killian Doherty

Football for Hope Centre in context , Kimisgara, Rwanda. Courtesy of Killian Doherty

Football for Hope Centre in context , Kimisgara, Rwanda. Courtesy of Killian Doherty

Therefore it has never been timelier for the South African architect, and teacher, Peter Rich whose very work draws heavily from its context’s, serving to bolster local communities it resides within, to now re-visit Rwanda to conduct a workshop and a lecture on his work with the Kigali Institute of Technology (KIST), also in conjunction with the University of Arkansas School of Architecture. Peter Rich’s work has established an architecture which is uniquely African. Influenced directly by an understanding of spatial hierarchies and aesthetic qualities of African tribal settlements, he works directly within the community, sustaining the cultures and traditions re-emerging in his buildings. His methods are not only due to his empathy for marginalised communities, but are methods which are a forceful architectural response to the new problems posed by contemporary global development, where a disintegration of identity, culture and community is characterized by homogeneity of place.

Approach to Football for Hope Centre. Courtesy of Killian Doherty

Wall Detail to Football for Hope Centre. Courtesy of Killian Doherty

During his visit, Peter was drawn to a place with a particular convivial spirit as the subject for his workshop; the community of Kimisagara, in the centre of Kigali. Kimisagara is the most densely populated, disadvantaged area in central Kigali with few opportunities for young people with alarming school dropout rates. It was in Kimisagara, in the unfinished ‘Football For Hope Centre’ for Esperance, that Peter chose as the venue to give his lecture about his work to the students of KIST, Arkansas and the community of Kimisagara.

Peter in community room of ‘ Football for Hope’ centre. Courtesy of Nerea Amoros Elorduy and Killian Doherty

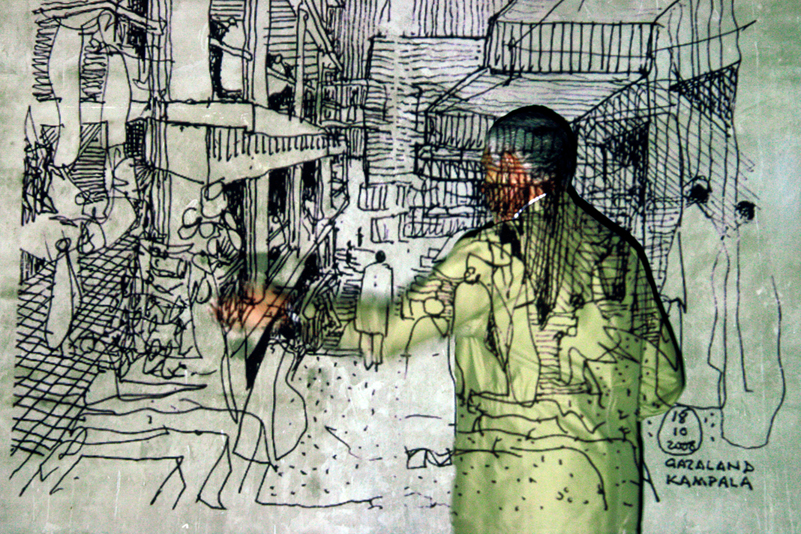

‘This lecture in relation with the exhibition LEARNT IN TRANSLATION draws on Peter Rich’s extensive personal and professional career, through his drawings and travel sketches, models and photographs. Rich’s working methodology emphasizes the importance of community engagement and research. Part of this process is intensive observation of people and environments, and documentation of the context for a project through sketching and measured drawings.’[ii]

Peter Rich Lecture – Courtesy of Nerea Amoros Elorduy and Killian Doherty.

Peter Rich’s work is influenced by his time spent with various South African tribes; the Kennedy house is planned around diagonal geometries regulating views to the ocean beyond, just as the spaces within an Ndebele tribal dwelling are diagonally arranged around the dominant space of the woman to reinforce the females position in the homestead. The sublime Mapungubwe Interpretation and Visitors Centre in Limpopo South Africa, which honours the site of an ancient trading civilization, evokes the circular domed forms of kraal settlements of dispersed African tribes. Yet in Mapungubwe it is in the very construction of these domes, that Rich’s work transcends tectonic form or space-making, by intervening and empowering the communities within themselves. At Mapungubwe the use of local soil to create stabilised earth tiles was employed to construct vaulted arches (a technique pioneered by Rafael Gaustivino) but which were built entirely with unemployed, unskilled labour within the local community, in turn learning new trades which they continue to use today.

Mapungubwe Interpretation Centre Mapungubwe National Park, Limpopo, South Africa, 2002-2010. Courtesy of Peter Rich Architects

Peter Rich Lecture – Courtesy of Nerea Amoros Elorduy and Killian Doherty

Peter Rich’s work cross fertilises modern architectural practice with the traditions of local identities and doing so , it underpins and preserves their ability to withstand the cultural attrition of globalisation; it is these lessons which the Rwandan 2020 urban vision needs to draw from. The current trajectory of the 2020 Masterplan, with its imported generic architecture, bears little relevance to the day to day living patterns and socio-economic abilities of the majority of the population (87 per cent of Rwandans live in rural areas and rely on subsistence farming), yet continues to be the near-sighted architectural dogma of Rwanda. So much so that it has attained a sacrosanct status where criticism is frowned upon; to question the authorities’ methods of implementing its modernisation strategy means to question Rwanda’s ability to be ‘modern’ and criticism which is often misconstrued as an obstacle to distancing itself from its dark political history.

But it is not a question of whether Rwanda can be modern, but how it achieves modernity by a more inclusive and sustainable means achieved through meaningful discourse founded within critical thinking. In a landlocked country, with little resources and a burgeoning population with a density of almost 420 people per square kilometre, (compared with that of South Africa with a density of just 41.4/ km2) land scarcity is an unsustainable problem; strategies of densification without re-locating the rural population into its few urban centres do appear to form a part of any national agenda for development.

Cognisant of such matters relating to Kigali’s re-invention, the Department of Architecture at KIST attempts to relay to the Rwandan students, the importance of preserving cultural identity as a component of one’s social responsibility as an architect , particularly through open lectures such as the one by Peter Rich. Composed of architects from MASS Design Group, lat 45N Architects, General Architectural Collaborative, Sharon Davis Design Studio and Architecture for Humanity, all of whom are building their own respective projects across Rwanda, it is their collective pursuit that the diverse traditions and identities of the rich Rwandese culture does not become a thing of memory.

Left to right: Architects Peter Rich , Killian Doherty and Toma Berlanda (Lat45N Architects) – Courtesy of Nerea Amoros Elorduy and Killian Doherty

Killian Doherty is an Architect working for Architecture for Humanity. Having worked in Stockholm, Dublin, and London, and completing a Masters in Architecture at the Royal Technical College (KTH) in Stockholm, he volunteered with a grassroots organization on the post-katrina reconstruction of New Orleans. He is currently designing and constructing a community sports facility in Kigali, Rwanda. A visiting studio tutor at the KTH in Stockholm, Gothenburg, University of Johannesburg and KIST (Rwanda), Killian has exhibited his work in Ireland, Sweden, USA and Canada.

Killian Doherty is an Architect working for Architecture for Humanity. Having worked in Stockholm, Dublin, and London, and completing a Masters in Architecture at the Royal Technical College (KTH) in Stockholm, he volunteered with a grassroots organization on the post-katrina reconstruction of New Orleans. He is currently designing and constructing a community sports facility in Kigali, Rwanda. A visiting studio tutor at the KTH in Stockholm, Gothenburg, University of Johannesburg and KIST (Rwanda), Killian has exhibited his work in Ireland, Sweden, USA and Canada.

References

[i] A.Tzonis,L. LeFaivre (1990) ‘Why Critical Regionalism Today’. In: Leach, N. et al. eds. Rethinking Architecture. London : Routeledge, p.484

[ii] Extract taken from Peter Rich’s forthcoming monograph

Good work Sir!

we are missing you at KIST

good attempt mister and i appreciate ur participation in architectural domain